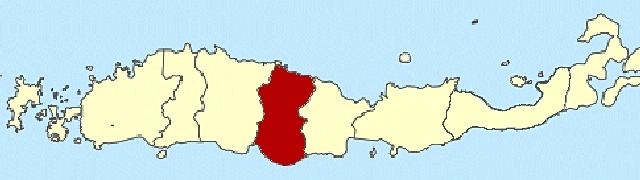

Ngadha region - marked by great geographical and ethnic diversityThe administrative unit called Ngadha Regency, in the eastern part of western Flores (east of Manggarai), these days covers two culturally and historically distinct separate areas, Ngadha proper and Nage-Keo - with which we deal separately. In the colonial era these two areas were ruled by separate rajas, with their respective seats at Bajawa and Boawae. The region is home of two large volcanoes, Ebulobo and Inerie, that dominate the landscape and shape the climate. The zone is marked by great differences in altitude: settlement range from sea level to nearly 2000m (6000 ft), with concomitant differences in temperature and vegetation. It is also marked by an extreme ethnic diversity, caused by small scale invasions in prehistoric times of people from afar, and by the jungly, mountainous terrain which in the past made covering more than a few miles a taxing and hazardous undertaking. As a result, there are so many small ethnic entities, marked by distinct customs, dialects and cultural products, that they have not even been fully charted. The fact that travel on Flores can still be a challenge helps this situation to persist. The characteristics of the terrain have also led to rather pronounced isolation of the region, and left it economically backward. When we visited the Ngadha region in the early 1980s (during the rainy season, which did not help), it offered a singularly depressing aspect. All we saw, with the exception of a few zones in the main town, Bajawa, located in a bowl and an administrative centre already in colonial times, pointed at crushing poverty, protracted hunger and debilitating illnesses. In hamlets at the higher elevations villagers sat huddled in front of their rickety huts under leaking palm thatch, clutching some cheap cottons and plastic sheets about them to ward off damp and the chilling cold. In the marketplaces there was precious little on offer. It was quite common (as it was in most regions of Flores, and on other islands in Eastern Nusa Tenggara), to see a seller sitting behind a single clutch of bananas or a small pile of areca nuts, patiently, and no doubt often in vain, waiting for custom. Many children had the extended bellies caused by chronic malnutrition, many grown-ups the caved in chests caused by tuberculosis. We saw no beautiful textiles anywhere, just cheap and flimsy Javanese cottons, and some semi-industrial ikat textiles made with chemical dyes. Photographs from the early 1900s, such as those in the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, available on Wikimedia, show that in those days as well the people of the Ngadha area seemed to dwell at subsistence level, also culturally, with little in the way of decoration.  Ngadha women spinning and weaving plain cloth for daily wear. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence."; The ikat textiles of Ngadha - sought after naivetyCloth production in Ngadha was helped by the fact that in the low-lying areas cotton can be cultivated, whereas indigo grows well in the temperate zones at middle elevations. Apparently Morinda citrifolia, the common source of red dye in the archipelago, does not grow well here. It certainly is hardly ever used. In the old days, daily wear in the Ngadha region was a plain, stark indigo sarong - which very few people consider collectable. However, the region is also home to a type of ikat cloth that is decorated.

Ngadha - a curiously simple, 'nude' languageNormally when we study a region's cloth, we would not be very interested in its linguistic particularities, but in the case of Ngadha, and also Keo, the language is of interest because its characteristics reinforce the image of a people with rather limited development. These two languages are very odd in that they use no prefixes or suffixes (the way of creating new words by tagging bits on to words either back or front, as in per-form or child-hood), whereas the Austronesian family of languages to which they belong is quite generous in the use of affixes. Two of the closest relatives, Malay and Bahasa Indonesia, use prefixes and suffixes quite intensively,

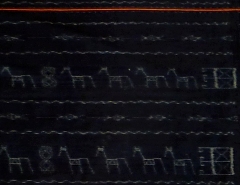

Tradition still holds - and affords statusMost of the ikat producing villages are located in the temperate, middle elevation zones where indigo cultivation is possible. The best known are Jerebuu and Langa, located in a valley under the east flank of the Inerie volcano, and Lopijo and Toni, tucked behind the rim of mountains that surrounds Bajawa. The latter are still very isolated and conservative, still using indigenous cotton and indigo only. The cloths from these localities are admired throughout the Ngadha region - and nowadays in New York and Singapore as well. An interesting tradition in the Ngadha region holds that in youth one is limited to plain or nearly plain cloths, and as one advances in age, after various levels of initiation accompanied by great feasts, can start to wear more intricate, more prestigious cloth. As Roy Hamilton states in Gift of the Cotton Maiden, "The most costly types of feasts [such as those requiring the slaughter of buffalo] were only within reach of the upper strata of society, so the garments associated with these events were essentially markers of aristocratic status. Today informants are reluctant to talk about such class distinctions, which no longer carry the weight of traditional law, but there is still a sense in some communities, that the most prestigious garments are appropriate only for individuals of high social standing." After making a feast involving buffalo slaughter, a man was entitled to wear cloths decorated with narrow bands of jara, horse, motifs. | ||||||||||||